I’m right now working on a baby blanket for a dear friend. Instead of going to the craft store and buying some big ol’ skeins of acrylic, I decided to be totally crazy and knit the blanket out of an organic merino that I handspun myself. And I don’t use a spinning wheel. I use a top-whorl drop spindle. The yarn weight is fingering size or thereabouts. Between the yarn weight and the intricacy of the knit (a basketweave) and the fact that I have to repeatedly stop knitting to spin up more yarn, to say this blanket is taking awhile to finish is an understatement.

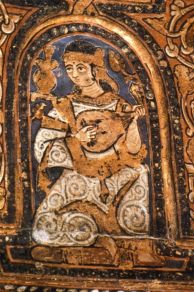

The Royal Palace in Palermo was renowned in the Norman era for its tiraz, or silkworks, and the island produced a lot of silk, in raw materials (reeled silk and yarns) and in finished fabric. The amount of silk used by the palace actually amazed visitors to the island; Alexander of Telese famously noted that during the coronation feast of Roger II, even the servers were clad in silk. Though the embroiderers at the tiraz seemed, especially in the Norman later years, to be eunuch males (ibn Jubayr interviewed one of these embroiderers when he visited Sicily in the reign of William II), many of the weavers, and definitely the spinners, were women and girls.

And one thing knitting my blanket and my take on the cap of St. Denis has given me insight into, every single pair of hands that could possibly produce threads and yarns were probably needed to keep the tiraz’s production up to speed. Most of the scholars who have written about the tiraz are often men and definitely not engaged in fiber arts. I don’t think they understand just how intensively every woman and girl needed to spin and reel, and how long this takes.

This, my friends, is a degummed silk cocoon in which the worm has been allowed to get out:

Because of the closeup, this looks much larger than it actually is. It’s actually only about two inches long and fluffy because the fibers have been pulled out in the action of taking it out the bag (where it stuck to the mass of cocoons in there). I’ve angled it so you can see the open end. Handling it is very interesting; the fibers catch upon the slightest roughness on my fingertips. Shea butter is my friend.

This is my spindle. That’s about half a cocoon hanging off there, the fibers of which I am drawing onto the spindle as singles, and then using a modern-day ply on the fly technique to make into a 3-stranded yarn for knitting. That’s the result of about 20 cocoons so far.

This type of cocoon would not have been used by the spinners of the tiraz, however; because the worm was allowed to chew its way out, there are many short and broken fibers. Because of this, instead of getting a nice long continuous fiber when I spin, the short and broken fibers produce a thread that’s slubby. What the spinners would have used was reeled silk. Let Cindy Myers, the Silkewoman, show you her method of how to reel silk from cocoons and what reeled silk looks like.

Think of all the silk that had to be reeled, twisted, dyed, and woven to produce King Roger II’s cloak. Really think about this, and you can understand why Roger’s palace (and the palaces of William I and William II) were filled with mostly unnamed women and girls (we only know the regents such as Adelaide and the queens such as Elvira). Whether Christian, Muslim, or Jewish, noble, free woman, or slave, they weren’t sitting on their butts praying and embroidering (the noble Christian ladies), bathing in fountains and eating peeled grapes (the Muslim slave girls) and waiting for the king and his warriors to get home. We already know that in 1147, when the Normans sacked Thebes, hundreds of silk workers, mostly women, were taken back to Palermo to help improve the tiraz. But there was a tiraz at the palace when the Muslims held the island, and after the Normans conquered the island, they certainly would have wanted to continue such a prestigious – and lucrative – business.

One thing that I’ve built into my persona, Adelisa Salernitana, is that she spins silk yarns and threads as a supplementary source of income and as an activity as a royal lady-in-waiting. It is known that in the nearby Fatimid court, royal women did spin; famously, Rashida, the daughter of the caliph al-Mu’izz, was said to have “earned her living from spinning yarn and never laid a hand on anything from the royal treasury for her subsistence.” Incidentally, her sister ‘Abda has reputed to have at least 30,000 pieces of Sicilian cloth at her death (“Women and the Fatimids in the World of Islam,” by Delia Cortese and Simonette Calderini).

Keeping the women gainfully occupied was also a concern of the Fatimid vizier al-Afdal, who at his death in 1121 had among his effects two trunks full of gold needles for the use of the female slaves and the women of his harem.

Here’s another example of how important this work was even in upper class households. A century after Roger II lived, the Damascene scholar Shihab al-Din Abu Shama composed a poem in praise of his wife, Sitt al-‘Arab bt. Sharaf al-Din al-‘Abdari. He extols her noble lineage, her wisdom, her mercy towards orphans, and her many virtues, including her contribution to the household income. He writes:

She always attends to household chores

despite her youth she shies away from nothing

tiraz embroidery, needlework with golden threads

cutting cloth, sewing and spinning

She moves from this to that and from that to this

not to mention the cleaning, the cooking and the washing.

(“Marriage , Money, and Divorce in Medieval Islamic Society,” by Yosef Rapoport)

I reason that if Adelisa wanted to build a life for herself and her soldier-husband outside the court, she had to raise money, and the best way for her to do that – and the most traditional – was by spinning. With a royal workshop to be supplied, threads she spun would have gone into secular and sacred textiles, to her profit.

en’t had a lot of time to do much in the way of research lately. I keep trying to change that, but overall, I am a lazy lump and being a freelance writer and editor, I have clients to keep happy, because eating and keeping my bills paid is nice.

en’t had a lot of time to do much in the way of research lately. I keep trying to change that, but overall, I am a lazy lump and being a freelance writer and editor, I have clients to keep happy, because eating and keeping my bills paid is nice.